The Legacy of Public-Private Partnerships in The Bloomberg Mayoral Administration

Graduate Thesis, N.Y.U. Center for Global Affairs

Abstract

A Public-Private Partnership ( P.P.P.) is a unique infrastructural mechanism which forges a profit-seeking rapport between a public entity and a private institution for a joint project. These permutations can be amoebic as can be their results: highways, transportation solutions, hospitals, and commercial buildings have all been manifestations of P.P.P. incentives.

P.P.P.s use innovative, and often unorthodox, methods of financing certain projects, including the utilization of Special Purpose Vehicles, alternative asset funding, and “competitive”- like city tenders to accomplish their goals. Various agreements and elements are imperative for P.P.P.s to succeed; these entail concrete Partnership Agreements & Charters, Ownership structures, methods of financing, contractors, and appropriate oversight. Despite their ostensible complexities, Private Public Partnerships can be harnessed to unleash profitable results for the private partner and expedited, robust project completion for the public entity.

The Mayoral administration of Michael Bloomberg, which lasted in a transformative era between 2002 and 2013, is the lens through which we shall examine these project structures’ societal impact in New York. Michael Bloomberg, who had extensive experience in the private sector coupled with a venerable reputation, directed his executive team to maintain their strong ties in corporate and private expertise. Bloomberg and co. believed that reappropriating private sector attention to New York City could be the answer to some of its prominent quagmires in the aftermath of September 11th 2001, notably in infrastructure, the environment, and data. Certain P.P.P. triumphs include the promotion of the Central Park Conservancy, the High Line, the development of Hudson Yards, and many more.

How have the aforementioned initiatives aged? What were the successes and failures of advocating such experimental methods? Examining Bloomberg and Co.’s legacy through their insertion of P.P.P.’s across the city -- with a megapolis like New York as their testing ground, no less -- is unequivocally pivotal in understanding how feasible P.P.P.s are across mega-cities. Additionally, magnifying the ulterior contextual conditions of New York in 2002 is instrumental in understanding why P.P.P.s were not just an option, but a necessity.

During Mayor Bloomberg’s unprecedented 12 years at the helm of New York, the city triumphantly resurged from the aftershock of era-defining terror attacks and valiantly re-asserted itself as a prosperous powerhouse. Initially dented in both debt and spirit, Bloomberg ushered in a zeitgeist of unbridled growth and renewal, with the private-sector being his greatest ally in bringing his initiatives to life. As fortunes rose, so too did rent prices, new skyscrapers, and, according to his critics, the reality of a sanitized New York meant only for multimillionaires.

Introduction

Cities around the globe possess a uniquely malleable, amoebic nature. As nuclei of commerce, culture, transportation, and the livelihood of millions, cities brandish an organic sort of being -- a result of the constant life on display through its motion. The manner in which we all fundamentally interact with cities will be corollary to the macro-socio economic trends: the surging level of uncertainty in our world regarding the climate crisis, migration, emergent diseases, access to equitable education, and a proliferating gap between registers of wealth will only compound its magnitude onto urban areas.

In a report published by the United Nations’ Department for Economic and Social Affairs, 68% of the world’s population will live in cities peopled by at least 1 million people in 2050. This is a substantial leap from today’s figures, which indicate 55% of the world’s 7 billion people are currently of urban populaces. Furthermore, the oncoming Malthusian tidal wave knows no geographic limits: countries that were once branded “emerging” will have sufficiently emerged, Gross Domestic Product and Human Development Indices will have skyrocketed, and young populations are projected to embrace urbanity. Merely three countries, India; China; and Nigeria, will account for up to 35% of this statistical increase, as erstwhile rural populations flock to cities thanks to broadening jobs within public and private sectors.

The enormity of this shift cannot be understated, and the very caliber of how cities act will fundamentally be transformed across the proximate few generations. For the cogs of a city to run smoothly, several infrastructural foundations must be in place -- the pillars upon which the basic necessity-based functions rely on. The efflorescence of “megacities” like New York, London, Tokyo, Los Angeles and Shanghai have these to thank for their tremendous success.

As the unstoppable trajectory behind this pattern continues, and mega-cities along with emerging metropolises call themselves home to an even more robust majority of the world’s population, more innovative solutions will be required. Ascertaining the stability of said ‘pillars’ that guarantee basic societal and economic harmony will be of utmost importance. This is no novel concept -- the intelligentsia of the world is rallying together to address these concerns in an efficacious manner. In an eminent “Imagining the Cities of the Future” dossier by McKinsey & Co Joe Frem, Vineet Rajadhyaska, and Jonathan Woetzel detail a quartet of principal challenges all cities will have to inevitably confront as we lurch towards our uncertain future. Two of these issues act as a balanced dilemma and panacea.

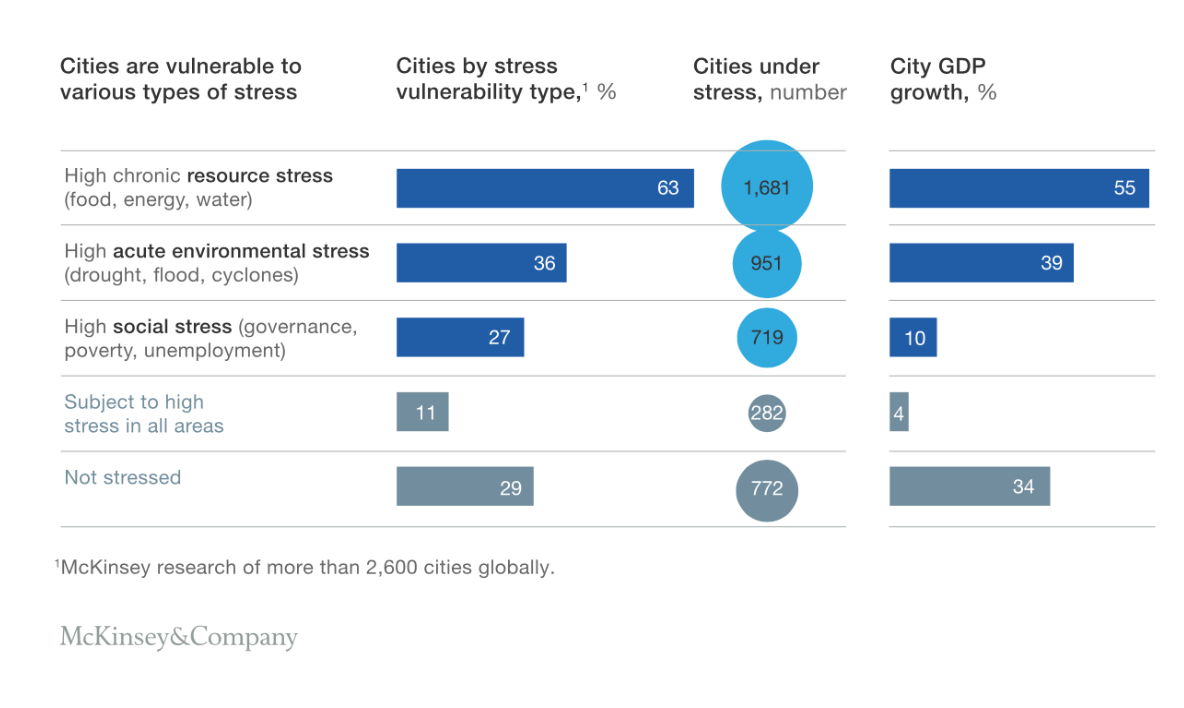

The first regards the various symptoms of “stress” that cities will undergo as a result of crippling population and consequent resource consumption. These are illustrated in Fig A.

Fig A: Stress Metrics Infographic. Extracted from McKinsey & Co., “Imagining The Cities Of The Future”.

Resource stress regards the conventional use of water, energy and electricity. Environmental stress concerns potential disasters lurking on the horizon to which proper disaster-resilience efforts confront. “Social”-based stress entails poverty, governance issues, and unemployment. These stresses are the natural mandate for solutions to follow at a city-based level, and are the overarching rationales for legislation. Of course, the report details that these stresses often synthesise to form multi-pronged hydras which in turn obstruct further productivity and growth -- cities, particularly those in emerging countries, will be tasked with accommodating growing populations and addressing these stresses which hinder the development of their own remedies.

The second component of the “Cities of the Future” report is not so much a challenge as it is a bounding opportunity, with the proviso that it is managed correctly. Disruptive technologies, as they are formally labelled, have the capacity to ameliorate the issues that city governments struggle with the most. Energy storage, fundamental assured internet connectivity, 3-D printing to facilitate the rapid production of manufacturing materials, and the expedient potential of transforming last-mile commutes by way of autonomous vehicles are but a handful of the multifaceted effects technology can be a harbinger for. Cities that implement these sorts of solutions have found themselves being given a certain positively-geared epithet -- “Smart Cities”. This buzzword has proverbially launched a million ships and catalyzed a plethora of integrated-service initiatives.

Furthermore, these ideas are derived from mixed sectors: public agencies have displayed more of a proclivity to support Silicon Valley-esque regional incubators in the pursuit of making their city more attuned. Big Four consulting firms, tech behemoths, NGOS, and many more have been partaking in a rat-race to forge the greatest, sustainable, and scalable solutions in aiding cities on their quest to, as Deloitte puts it, “hum” in a fine-tuned manner.

Non-state actors that operate at a regional level, like CIV:LAB, have pioneered the shattering of boundaries to create non-siloed ecosystems wherein the aforementioned organizations work together in coherent manners. Their efforts bore fruit in the creation of The Grid, a membership network which counts Google, Verizon’s 5G Labs, Citibank, NYU’s Urban Future Labs, and many more as constituents.

The above information leads us to grapple with certain quandaries. What is an imitable method of erecting smart-solutions for all the proximate stresses that overpopulated, high-consumption cities will face? Moreover, are there any exemplary efforts we can cast as precedent to learn from? Have the various experiments megacities can afford to audaciously engage in prompted any epiphanies? One such experiment of grand proportions was the frequent employment of Public-Private Partnerships during the Mayoral tenure of Michael Bloomberg in New York City across his three terms.

At its philosophical crux, the future of cities lies in its exoskeletal structure. The encouraging trends point to the fact that this very blueprint is more controllable and accessible than ever before. The presence of one key aspect, the genetics of which is the focus of the following paper, has the necessary multitudinous flexibility to bring about unbridled, transparent, and perpetual growth. Deciphering the advantages of these arrangements is pivotal in comprehending how Public-Private Partnerships, or P.P.P.s/P3s, are instrumental in the future of urban financing. If the utopian, idealistic marriage between the public and private sectors is a galvanizing force for good, the various stresses and dilemmas cities incontrovertibly have to face can be combated effectively and mechanically.

The fabled, grandiose notions concerning the cities of the future may be that more attainable if governments adopt P.P.P.s as the main asset in their societal toolbox. While the mere existence of P.P.P.s is a relatively recent phenomenon, they have been tried and tested to wondrous avail in a metropolis that epitomizes the notion of a city: New York. While Mayor Michael Bloomberg is no longer at the helm of the 9-million strong diverse urban sprawl, the enduring legacy of the private-sector acumen he and his administrative officials brought is relevant as ever as mounting issues surrounding inequality, preservation, transportation, and energy emerge as the new frontier of urbanity.

Examining their efficacy and legacy is vital to understanding their replication. In times when private-sector haughtiness is met with skepticism and public-sector initiatives fail to gain expansive traction, P.P.P.s act as not only our most promising tool, but our necessary salvation in an incalculable future.

II. A New Dawn, A New Mayor

The crisp, halcyon morning of January 1, 2002 felt a gust of optimism in the aftermath of the most traumatizing event in modern history. As Mayor-Elect Michael Bloomberg ascended a vermillion plenary outside his new office, his predecessor and endorser-in-chief Rudy Guiliani took a seat nearby. A few hundred feet away were the remnants of a zeitgeist- defining catastrophe that changed foreign policy, security, espionage and the mere definition of ‘terror’ forever.

The September 11 attacks on New York and the country as a whole had crashed the largely optimistic era of economic and social growth to a horrific halt. The nation and the world rallied around the recuperative cause of New York, and the transition of the Mayor’s sceptre at this fragile time was viewed with an amplified pedigree. Bloomberg, wrapped in conservative attire complete with a scarf to buffer the winds of pressure whirling his way, was fully cognizant of the expectation that was mounting. While Bloomberg had the blessing of the elder statesmen present, the man at the wheel before him had recently been crowned Time magazine’s “Person of The Year” and had been lionized as Rudy Giuliani, America’s Mayor. Beyond the persistent anguish the unshakeable memory of 9/11 continues to bring, everyone in the audience knew the same fact: Bloomberg had founded the eponymous multi-billion financial services empire, and it was time for someone to resuscitate New York with the same vigor as a private equity firm turning around a crippled business.

As a mercurial Independent strategically running on the Republican ticket, the usually laconic Bloomberg was conflagrant in his inaugural address: “Rebuilding our city will not be easy in this economic climate…[it will] require tough decisions in government, non-profit sector, business and labor. But the facts are clear: we will not be able to afford everything we want; we will not be able to afford everything we currently have”. This moment of profundity at the nascence of what would be a 12 year administration is something of a prophetic statement: a rousing call to all sectors to inform and help in a time of crisis. In this regard, the extraordinary circumstances warranted by the events of the preceding year may have contributed to the eventual popularity of P.P.P.s in the dozen years to come. In order to successfully medicate a city that had been shattered to its core, Bloomberg -- a titan of industry as rich as Croesus himself who had spent tens of millions on his own campaign -- would have to rely on a multitude of forces outside of his own pocket for any kind of financial bulwark.

Prior to examining the efficacy of these infrastructural models and the hallmarks of the Bloomberg administration, it is essential to dissect and conceptually master the technicalities of what constitutes a Public-Private Partnership. Exploring the ins and outs of what these instruments can do is essential in justifying their usage and scalability, as well as their downsides and vulnerabilities.

IIII

A Structurally In-Depth Examination of Public-Private Partnerships

The necessity of P.P.P.s stems from a similar axiom regardless of location or magnitude: a lack of funding and or expertise. Whether it’s a school, hospital, mixed-use building, mode of transport, or charitable initiative, cities and sovereignties are not innately meant to be experts on every corner of society. Their responsibility is to ensure the livelihood of their citizens, the prosperity of their economy, the safety of their neighborhoods, and the attraction and hopeful retention of the best, productive talent possible.

Yet, all these idyllic benchmarks arrive at a heavy price. Budgets need to be balanced and the unintended expenses of sporadic crime, damage, disasters, commensurate emergency services, and access to energy are just a handful of the litany of mitigative qualms. Oftentimes, governments simply lack the ambition and curiosity to attempt even the finest of ideas. With thanks to P.P.P.s, highways, medical facilities, schools, philanthropic initiatives, bridges, and restoration projects around the world have been brought into worthy existence -- physical deliverables that would have otherwise not have been feasible from the repetitive binary of one sector doing its utmost.

Tony Boivard of the Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships writes that although mixed-sector procurement projects have dated all the way back to ancient civilizations, the recent modern infatuation with them derives from a U.K-based predecessor of a different name: Private Finance Initiatives. Popularized in the 1990s as a sleepy, underused program through the John Major and Tony Blair governments of the Conservative and Labour Party respectively, PFIs received backlash in a country that knew the bitterness public vs. private schisms created all too well. A decade earlier, the “Iron Lady” Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had passed sweeping free-market reforms, chiefly privatizing the energy industry overnight. Her decision to this day is met with acerbic views from Labour-supporting critics, tarnishing her posthumous legacy Rather expectedly, PFIs were met with vehement opposition from journalists, politicians and citizens alike. In a September 2007 Op-Ed for the Guardian by George Monbiot, the author writes that the birth of P.F.I.s was a measure of equanimity to balance the books -- and parliamentary temperaments -- at a time when hospitals, highways, and other services were sorely underfunded. Private sector companies would bear the financial burden of basic essential services and then “rent” them back to the government in a traditional, simple arrangement. However, A veritable P.P.P. calamity soon occurred in the subterranean passageways of London in the late 1990s. The plan consisted simply of inviting private-sector investment onto certain Tube passageways -- an anomalously Thatcherite policy for her Labour rivals to bring to life. The surge of optimism that accompanied New Labour’s raucous election victory in 1997 soon turned sour as the Transport for London Authority blamed the government for direly mismanaging an otherwise promising Partnership. A lack of continuous oversight, virtually non-existent metrics of tracking, feeble communication between stakeholders, as well as being decried as “prohibitively expensive, fatally flawed and dangerous” by then-mayor Ken Livingstone descended the underground project further into a pit of despair. It is feasible that Bloomberg’s team probed into this failure as an example to learn from.

While there is no one single source that explains how P.P.P.s emerged and spread across nations, it is widely accepted that several governments had some method of hybridizing the public and private sectors, possibly all contemporaneously from the 1970s onward. “The modern era of P3s may have begun in 1979 document known as the Office of Budget & Circular Management A-96”, writes Michale Lafaive of the Mackinac Sector for Public Policy. This federal proposition permitted public construction outlets to cooperate with private actors in a manner not formalized at a national level before in the U.S.

In an issue of Comparative Politics from April 1995,, authors James O’Leary and Machimura Takashi detail a Japanese financial phenomenon known as “Daison Sekuta”, which translates to “Third Sector” -- an “invisible hand” sort of actor on the market that can act as a revolutionary tool of leveraging government and business talent effectively. In fact, the researchers find evidence that the Japanese government was willing to entrench “Third Sector” organizations into solid legal standing: “A third sector Japanese organization can have a legal standing as a corporation (Hojin) under civil or commercial law”.

As the 2000s passed, P.P.P.s were ideated across over 50 countries around the world, with academics and economists alike struggling to explain the massive buy-in. Perhaps the surge of capitalist fervor had outranked governments across the board, and the latter had no choice but to look to the captains of industry for help in resuscitating their own static failures.

Individually, the public and private sectors both suffer from tantamount reticence in their projects: public services, be they transportation, energy, healthcare, or education, are plagued by being bereft of sufficient funding and talent. What may have started off as a practically cohesive plan ends up in the dustbin and soon transforms into a miasma of scandal, burden and criticism.

Similarly, the private sector’s initiatives are often dismissed as being profit-seeking, invasive on daily life, inaccessible to the common man or woman, and as having spendthrift motives -- common platitudes that invoke distrust amongst the public.

However, P.P.P.s offer a solution to this. The synthesis of talent, knowledge, management, finances and outcomes are favorable for all involved -- every party privy to the agreement benefits from it in some way. The Yale Insight’s “How Do You Build Effective Public-Private Partnerships” article, from the Yale School of Management, provides a digestible and concise definition for what P.P.P.s, often referred to as P3’s, are capable of: “the public-private partnership...lies somewhere between public procurement and privatization. Ideally, it brings private sector efficiencies and capital to improving public assets or services when the government lacks the upfront cash”.

These unique agreements can alleviate onerous monetary burdens, provide services that are of a higher quality, and make for a domino effect on increased, encouraged collaboration across various industries.

Risks of P.P.P.s include imbalance of effort, funding, knowledge; failure to meet deadlines, hijacking by one party, and stagnation of progress due to political and or unforeseen circumstances.

P.P.Ps are capable of operating in any sector and in any context. The notion of the public and private sectors collaborating on projects is by no means a novel one, but P.P.Ps add a required level of rigidity and accountability in the convoluted process of turning projects into realities.

IV. The Partnership Agreement & Charter

The foundational promise of a P.P.P is in its conciliatory agreement. These are manipulable and flexible; the World Bank’s Private-Public Partnership Resource center states that “there is no one widely accepted definition”. They proceed to state that the keywords in their accepted standard of what qualifies as a P.P.P entail the private sector “bears a significant amount of risk and management responsibility...renumeration is linked to performance”. The Yale School of Management’s philosophy on P.P.Ps is that they are contingent on contractual binding: a public partner delegates what would normally be its own responsibility onto the private partner, as defined by a codified agreement prior to the establishment of the project. The wording is multifarious, though the goals are the same -- an expanded chart of common P.P.P. definitions can be found in the appendix of this paper in Fig. 1.

David Gage, the author of “The Partnership Charter: How To Start Out Right with Your Business Partnership (Or How To Fix It)”, stresses that regardless of the modified definitions that are adopted, embracing a fortuitous initial “Agreement” or “Charter” is imperative (p.40). The two differ slightly, though they are equally capable of mitigating issues down the line. “Agreements” are often more quantitative, common, and legally binding. Their principal focus is to act as a dossier of reference for project goals, finances, benchmarking, and obligations that the two or more parties shall undertake.

Charters, on the other hand, act as cordial instruments to both infuse camaraderie and ensure transparency -- in the words of Gage, charters enforce a “collaborative spirit”. The following is Gage’s juxtaposition of the two:

Fig 1. David Gage's Differentiations between Charters and Agreements.

Fig 2. Various types of the most common P.P.P.s.

Fig 3. A spectrum of public-private involvement across project types.

As the chart on the left suggests, the erection of the charter is a maneuver of affability and warmth. It suggests an intent to work together, while the agreement conveys the intent of completion. At this point, upon signing the documents, the partnership has manifested and the project is underway. Gage recommends that all P.P.P.s feature both as a kind of positively inclined gesture, though the sole Agreement is usually the guaranteed feature at the dawn of any P.P.P.

The next progression in the relationship, which is typically configured within the Agreement itself, is the type of Partnership Structure that shall be taken on. This is not so much a determinant for the success of the project as it is a degree of certainty for its life. Dr. Alexandru Roman of California State University at San Bernardino in conjunction with the National Institute for Government Procurement brilliantly outlines some of the more ubiquitous Partnership Structures. These Structures are often referred to by an acronym which communicates its skeletal base, but also its teleological future in an instructive, simple manner. Roman’s effective compilation of the most utilized structures, complete with projects conceived, is found below in Fig 3.

As displayed in Roman’s chart, Partnership Structures can be as innovative and accommodating as the solutions they aim to provide. Each type of categorization, however, is accompanied by various advantages and disadvantages. In Design-Build (DB), a significant level of trust is delegated to the private partners for a project that the public sector has to answer for should matters go awry. The private sector receives a fee, but not much else in terms of ownership -- a profit-boosting, but still somehow costly, series of events for them. In the Design-Build-Finance Structure (DBF), the public partner is culpable for maintaining and operating large-scale infrastructure that they may not have been privy to planning; public officials may lack the requisite know-how to ensure the longevity of such a responsibility. In more complex iterations like Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Maintain (DBFOM), the private partner virtually controls every aspect of the project, from the construction to the minutiae of salaries for engineers who toil away on a single pipeline. The only kind of onus the public sector has to bear is a promise to ensure a tax exemption-status for it -- ushering in private investment may be more persuasive when additional costs are curtailed or done away with altogether. The various Partnership Structures can be metaphorically equated to thespian actors: in certain shows, an actor may play the lead; in others, they adopt a secondary, albeit still vital, guise for their co-star to shine. Similarly, these Structures consistently shuffle the precedence of whether the public or private sectors take the main stage. To complement the visual, a spectrum of private involvement extracted from Adjunct Professor Chloe Demrovsky’s Spring 2019 “Public-Private Partnership” course at the New York University Center for Global Affairs has been included in Fig 4.

This infographic portrays Structures of a similar nature, though it does so indicating how strongly each one involves the private sector. It is critical that the Structure and the delineated levels of involvement from both parties is expanded on and included in the erstwhile Partnership Agreement. P.P.P.s are destined to the ether of futility without one key ingredient, however: capital.

V. Funding

The financing portion of a Partnership is indubitably the most complicated aspect of its being. While the traditional variables surrounding funding encapsulate the usual concerns of how many players are at the table and when deadlines need to be met, the anomalous nature of a Partnership inevitably endears anomalous risk. Demrovsky’s materials for the previously referred-to course are useful in indexing the numerous considerations both sectors have to digest before pulling the lever to unleash necessary funds: What kind of financial guarantees lie at the end of the road? What kind of ensuring stability protects the project’s income stream? Will there be opportunities to refinance the debt and potentially offload the investment should the worst case scenario be met? (Demrovsky, “Session Six: Finance & Economic Development). Once these commitments and possible obstacles are addressed in dialogues between the two or more entities, the apparatus through which the funding will be delivered must be considered. Traditional, debt-incurring loans from the private sector to the public are often the weapon of choice.

Alternatively, the public sector could elect to include an “equity participation” clause: the public controls a segment of the project's equity, so as to not permit potential usurping by their corporate partners. Tax-exemptions, like those mentioned in the DBOFM structure in Fig. 3, are trump-cards the public sector can often play to mollify any kind of reluctance from their private neighbors. Regional and state governments, at the behest of private corporations wishing to avoid risky commitments, can offer loan guarantees to compensate the private agent, so that the corporation can recoup its investment even in a disaster scenario that renders the project itself paralyzed or stationary.

One question bubbles to the surface: shouldn’t the private sector, widely lauded as the cradle of modern innovation, bring some pioneering tricks or methods from its perfunctory business into the arena? The answer to this is that they do. Special Purpose Vehicles, or SPVs, are micro-appendages of larger companies. They act as “orphan” portfolios to delineate and detract risks and assets away from their parent overlord. In doing so, they assuage investors with the promise that, should the Partnership self-destruct, balance sheets will not be adversely distorted.

Sean Ross of Investopedia contends that the merciless, institution-sucking whirlpools of The Great Recession in 2008 prompted fund managers and C-suite executives to abandon conventional strategy when it came to avoiding liabilities. Ross strengthens his point by underscoring their salient invincibility to the forces of the market: “SPVS are considered to be bankruptcy-remote companies...little to no impact on the parent company if it goes bankrupt, and vice-versa”. An SPV to a corporation is what a colony is to a mercantilist country: a well-nourished, almost invulnerable offshoot that powers the mother company. It is an appealing option when compared to the all-too public pitfalls of sacrificing shareholder confidence when reporting losses on an earnings call. SPVs are not as much a means of stealth as they are merely a form of reorganization: they are strictly regulated and have to comply with local legislation on a tight leash.

Still, an SPV provides the potential for corporations and governments to experiment in creating their own bubbling cauldron of debt, equity, bonds, and or any other fiduciary instruments. The chance to engage in this while foregoing any major dent to the general health of a company -- at least, publicly --is a very opportune, compelling one.

Once the project has quite literally hit the ground running in terms of construction, and capital begins to pump through the arteries of the Partnership, tracking methods become both pragmatic and essential.

External benchmarking - before and during the completion of the project - is the preferred method of juxtaposition in seeing how theoretical Project X stacks up against existent Projects Y and Z. Strictly speaking, benchmarking practices are methods to ensure that progress is being made by comparing features and outcomes of the project to other successful iterations around the globe. Benchmarking is another technique appropriated from the private sector -- companies would use internal tracking methods to see how various projects, teams, and deliverables ranked amongst each other. In an excerpt from “Benchmarking for Best Practices” by Christopher Bogan and Michael English, the authors state that benchmarking is not only an “‘evidence-based’ view of performance throughout its life cycles…[which] practices produce exceptional results”, but also a “tool to identify gaps in the process to improve and enhance performance”. The encouraging trend is that, as more P.P.P.s are taken on, the more abundant a field of precedent there is for nascent projects to benchmark against. With this in mind, there are two focal methods of benchmarking available to Partnerships: ones that look inward, and others that look across industry equivalents. Ed Lette of the Business Resource Center of Texas and many others believe that liquidity ratios are portentous aspects of benchmarking practices that need to be observed. These mathematical calculations can inform lenders and partners about revenue stream patterns, assets, liabilities, and the fundamental relationship of how far their funding can go across an elapsed time. Realizations like these are difficult to grasp if the Partners are unwilling to benchmark and study predecessor-projects.

Benchmarking is also an optimal segue to examine the most important method of tracking: Assessing the financial implications of a Partnership during and after its unveiling is extremely vital to both entities, regardless of what kind of Partnership Structure (see Fig 3.) has been employed. At a simple, essential level, and for the sake of content brevity, a duo of corporate finance calculation formulae are often resorted to when interpreting how lucrative an initiative may have been.

The first of these is quite self-evident: Net Present Value, or NPV, “compares the value of a dollar today...with a point in the future, accounting for inflation and returns”. NPV has become a wieldy tool in the arsenal of Microsoft Excel analysts due to its compact, swift execution in forecasting the cash flows given a number of variables, and remains the industry standard in understanding financial implications. Project managers also conduct an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) calculation, which can be divided into Project IRR and Equity IRR. The former “signifies returns to all investors”; the latter aims to understand the “returns for the shareholders of the company” after outstanding debt has been paid off (“Public Private Partnerships in India: Ministry of Finance). Due to the often gargantuan-scale investments and projects that P.P.P.s inhabit, project teams often resort to using both to maintain as visible a financial frontier as possible. These percipient forecast methods contribute to key decisions and can often act as crow’s-nests in detecting future issues.

VI. Unveiling & Future

The final step of any P.P.P. concerns the implementation of something more abstract -- positivity and encouragement. At last, the highway, hospital, bridge, tunnel, amenity, or shopping mall has been completed -- it can now transcend into a normal sense of being to serve the greater public good. The end of a P.P.P.’s construction is by no means the end of a Partnership in the slightest, however. As addressed in the Partnership Structure paragraphs, Partnership Agreements often include clauses, contingents, and further bonuses over the course of decades. Here we can harken back to the Structure types: some P.P.P.s, upon completion chiefly by the private sector, are then returned and formally deemed as public property, and vice versa. More complicated Agreements include a nexus of trade-offs, deals, shuffles in ownership, as well as sponsorship opportunities and further concessionaires for private sector actors in the future.

That being said, the preceding text has served to issue a general, macro-scale overview of P.P.P.s, though in the coming years even more experimental and imaginative methods of how these unique agreements are made could very well emerge. They are customizable, idiosyncratic, and consistently evolving as novel technologies and concerns surrounding smart-cities enter the foray of inventiveness. For every successful P.P.P., however, there are scores that have failed. Dr. Roman’s report cited earlier that horrible consequences can come at the behest of poorly-communicated, lackadaisical partners who enter Partnerships purely to make a quick buck. Dr. Roman, however, decides to end his report on a more buoyant than cautionary note: “Public procurement specialists must...scrutinize in detail with a high level of skepticism...safe partnerships are guaranteed to yield large benefits to the public sector”.

While this thesis does not yearn to provide an all-encompassing history of every single P.P.P.’s journey, it does wish to contextually express how experimental, flexible, and ultimately fruitful these arrangements can become for all involved by magnifying the efforts of Bloomberg’s mayoralty in New York. With a few exceptions, Bloomberg and his administration did not necessarily engage in the most complex Partnership Structures; perhaps the clunkiness of city bureaucracy to wade through prevented this. In the proximate chapter, we shall refocus our attention on the Bloomberg mayoralty as fertile ground for P.P.P.s to burgeon.

VII. Bloomberg’s Mayoralty & Reception: An Overview

A dozen years at the helm of the most tumultuous city on planet earth is difficult to assess. Through such a long, imperious time, it is virtually impossible to agree with every single policy, evade any kind of backlash, or please everyone in a metropolis that prides itself on diversity of thought just as much as it does diversity of people.

In recent times, complemented by the spontaneous run for the Presidency, a variety of literature has emerged in the mass media retroactively grading Bloomberg’s Mayoralty. Seven years have passed since Bloomberg stepped down as Mayor for Bill De Blasio to take the sceptre; and history has looked upon his Mayoralty kindly.

The following Marist College-conducted polls in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6 index approval ratings and attitudes towards general policy trajectory throughout the duration of Mayor Bloomberg’s tenure.

Fig 5 (Left) and 6 (above). Extracted from Marist Poll.com, 2011.

While Mayor Bloomberg’s mayoralty was vulnerable to the same pendulous upswings and downturns as any politician’s would be immune to over the course of 12 years or so , his approval rating and “right direction” feedback was overwhelmingly positive on average.

In tallying up the means based on the above figures, this paper can present that his average approval rating from 2004 (two years into his tenure) until 2013 stands at a rather impressive 51.813%. The equivalent figure for the “right or wrong direction” chart is a bemusingly identical 51.605%. Furthermore, a Quinnipiac University poll conducted in January 2014 cited that 78% of Republicans and 62% of Democrats registered in New York City would call the Bloomberg epoch a success.“‘Mayor Mike leaves City Hall with good marks. Two thirds of New Yorkers think his 12-year term was a success, that he made New York a better city’, said Maurice Caroll, director of the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute”.

To boast these key figures across the span of a three-term Mayoralty is not only impressive, but unlikely to ever be replicated -- primarily due to the fact that the New York City Council temporarily nullified the term limit clause in the State’s constitution for this one figure (“Council Extends Term Limits for Mayor”, CNN.com). That gesture in itself speaks volumes about his veneration amongst delegates and citizens alike.

In one of the long-form retroactive studies of Bloomberg’s career by Emily Stewart at Vox, the author finds it appropriate to divide the Mayor’s public persona into three comical, yet meaningful, “roles”: “Bloomberg the nanny”; “Bloomberg the cop”, and “Bloomberg the builder/ manager”. While these titles may be saliently facetious, they each act as accurate topical exposures to traits of his administration. With these as our milestones, we can briefly navigate through policies and key moments within his Mayoralty as a thematic means to segue into the usage of P.P.P.s.

First and foremost, Bloomberg believed his moralist values should inform policies in the city for better or worse; in this sense, he was the “nanny”. Following heartfelt words regarding the rehabilitation effort of Ground Zero nearby, Bloomberg’s focus shifted to one of the most subtle yet pervasive issues in the city and the state: quality of education. He “championed” charter schools, and eased the accessibility criteria for new, impoverished students to enter formal education. In something of a meta-move, his task force opted to give letter grades to schools as an indicator of their performance, and accelerated outreach programs to give lower-middle class families a choice as to which institution they would wish for their child to attend.

Similarly, in 2002 and 2012, Bloomberg sought to implement taxes on tobacco products and, famously, a vendetta against sugary beverage containers above a certain size. The former was a public health maneuver that struck a tone of integrity and necessity with New Yorkers and also increased the average lifespan by three years. The latter’s proposition was struck down by a state judge on grounds for being unfair to businesses that it would advantageously exempt. “Nanny” Bloomberg became a common epithet for the Mayor as citizens likened him to a stringent figure who spent his Mayoralty “banning trans fats, requiring calorie counts, kicking cars out of Times Square” (Stewart).

“Bloomberg the cop” envelops into a series of policies mired by controversy, even when his intentions were well-meaning. German Lopez of Vox analyzes the divisive “stop and frisk” policy, which legally enables law enforcement to examine individuals or groups in public without concrete evidence, and concludes that perhaps Bloomberg was merely “continuing the ‘broken windows’ philosophy embraced by his predecessor, Rudy Guiliani...his police commissioner, Ray Kelly, expanded stop and frisk significantly”. While Bloomberg later admitted he was wrong to support the movement which disproportionately targeted Black and Latin-ethnicity males, supporters argued a remarkable reduction in crime did occur. Intriguingly, social scientists, particularly those at the University of Pennsylvania, have attributed the perceived decrease in crime conveyed in Fig 7. to more policing and less stop-and-frisk encounters (MacDonald, “Does Stop-And-Frisk Reduce Crime?”). To add to Bloomberg’s woes, a New York Civil Liberties Union Report on “Annual Stop-and-Frisk Numbers” aggregates data from 2002-2019 and finds that an astonishing “9 out of 10 stopped-and-frisked New Yorkers have been completely innocent”. While stops have decreased (See: Fig. 11 in the Social Impact P.P.P.s chapter) following Floyd Vs. City of New York, in which police officers were required to adopt a number of behaviors and protocols should they apprehend someone on the street, the policy remains a smudge on Bloomberg’s Mayoral tenure.

Fig 7: NYPD Graph on Major Offences in N.Y.C., 2000-2018. Extracted From the BBC.Com U.S. Site.

That being said, as explored in the proximate section, Bloomberg et.al. had a redeeming measure in the form of a P.P.P. to help tackle the maelstrom of negative attitudes and stereotypes his own stop-and-frisk measure may have helped propound.

The last but most significant role of Bloomberg’s is one of the principal focal points of this document. It is not an overstatement to declare that, across his twelve years at the mantle of New York, Bloomberg orchestrated several masterplans with an approach that was more bullishly Robert Moses, New York’s notorious steely “master builder”, than it was Jane Jacobs, the preservationist, soul-salvaging David to Moses’ Goliath.

Dramatic rezoning, construction permits, and lenient policies for behemoth real-estate developers in the wake of 9/11 were all part of the Mayor’s pragmatic vision to rebuild not just the World Trade Center, but also dozens of other commercial and residential areas of the city. While the Hudson Yards and High-Line projects are seen as the other glorified pinnacles of initiatives Bloomberg greenlit and supervised -- which shall be delved into appropriately later through P.P.P.s as a conduit -- there are countless examples of how the Mayor’s insatiable hunger for modern transformation had him walk out of City Hall for the last time in 2013 to a radically different city. The frontier of opportunity and functionality knew no limits, as sleepy, primarily family-owned store occupying-neighborhoods like Long Island City, Williamsburg, Park Slope, portions of the Lower East Side, and a rather dormant lot of No Man’s land north of Chelsea and south of Hell’s Kitchen -- soon to be known as the home of the most expensive development project in modern American history -- drew the attention of Bloomberg’s crosshairs. A strategic measure of the Mayor, which one could say provided the appropriate climate for the advent of P.P.P.s, was known simply as “rezoning”. The dramatic lengths taken to “rezone”, which translates to “reclassify the permissions on the land of”, are best encapsulated in by Abigail Savitch-Lew of City Limits:

“From 2001 to 2013, the Bloomberg administration recast the built form of New York by enacting 120 rezonings covering about 40 percent of the city’s land mass. Some were called “downzonings” because they reduced the allowable height and density of buildings in homeowner neighborhoods throughout the outer boroughs. “Upzonings” enabled soaring new high-rises in Williamsburg, Long Island City, and other central areas. In many cases, the Bloomberg rezonings did something of both—preserved the character on residential blocks while allowing higher buildings on central corridors.”- “Community Boards Reflect on their Votes For, and Against, Bloomberg Rezonings”, Abigail-Savitch Lew.

In a fettle of hyper-development fervor, Bloomberg and his associates decided to scout out any fathomable land that could be repurposed into residential, commercial, or mixed-use. Theorists trace the cataclysmic shocks of the September 11 attacks as being the propulsion of Bloomberg’s thinking: his “aggressive agenda” pushed for the city to seek out hosting the Olympics, the Democratic and Republican National Conventions of 2004, and the complete makeover of Manhattan’s West Side, from Battery Park to Inwood. “Only two out of those five came to pass: the Republican Convention and the West Side rezoning...But having those aspirations sent a signal to the world that New York would not slink away in cowardice after the attacks” (“New York, the Vertical City, Kept Rising Under Bloomberg”. WNYC).

In putting on his very own hard-hat, Bloomberg not only paved the way for mixed-sector collaboration and innovation through real-estate reorganization, but also ensured the field was ripe for the public and private sectors to engage in a higher number of opportunities together. Had these very specific contextual prerequisites not been in place, the emergence of P.P.P.s -- 21 major ones to be in fact under Bloomberg -- may not have been as triumphant. That being said, there is another reason why they ultimately did so.

Across the review of relevant literature employed to complete this thesis, a litany of words under a certain category have appeared. “Bankrupt”. “Underfunded”. “Sinking in its own mud”. The list goes on -- terms that unequivocally communicate a city in deep demise; a budget deficit comparable to the forlorn debt accrued in the 70s when New York was famously instructed by President Gerald Ford to “Drop dead” (Ford To City: Drop Dead, History.com).

. Compounded by the nightmarish consequences of terrorist acts, the city government found itself neck-deep in a torrential overload of debt after debt. Bloomberg’s predecessor, Guiliani, had not lessened the overwhelming budget imbalance either. Guiliani, as New York’s megaphone and recuperator in the wake of 9/11, had earned universal praise for his handling of the deadliest attack on American soil, and rightly so -- his determination, quintessential pugilism, and resilience in the face of disaster captivated the world. However, his financial management skills in effectively steering the city budget left much to be desired. In a last-ditch effort to pump resources into causes and urban committees he favored, Guiliani penned a disastrously exorbitant set of spending decrees worth $3.1 billion in excess of budget (Skine, “Not If You Count All The Years”). Accounting for the 9/11 attacks, this expenditure ascended to a hulking -$4.77 billion that a new Mayor had to somehow incur public favor with.

Were the seemingly avaricious measures Bloomberg’s administration took in rehabilitating the city the result of the quagmire this debt left them in? Surely, the public sector did not possess ample funds to manifest any of their desired initiatives. The origins surrounding where Bloomberg and his team discovered Public-Private Partnerships is murky and unknown, but one hypothesis we can explore in light of the aforementioned details is that they were forged to accommodate project proposals as a form of optimistic resurrection.

One very pivotal document, published by Bloomberg Philanthropies in 2013, is titled “The Collaborative City”. It acts as the most eminent, informative, and clear dossier on the role of P.P.P.s and their multifaceted compatibilities -- it shall be drawn upon numerous times henceforth, though not exclusively. The official rationale in this document for the flood of P.P.P.s is an answer as generic as it may be truthful: they cite Bloomberg’s expertise and credence in the private sector to thank. The so-called “central impetus” for the exhorting of P.P.P.s derives from the Mayor’s tendency to “shake up traditional bureaucratic structures to make them more entrepreneurial, responsive, and flexible” (“The Collaborative City”, p.5). In its introduction, the report does not elect to include the antecedent of 9/11 or Giuliani’s fiduciary pit. It adopts an ebullient, streamlined tone and is replete with infographics which give it the demeanor of a start-up pitch: a comprehensive guide on how Bloomberg and his team of all-stars managed to successfully install Partnerships to address both furtive and blatant needs near and far.

Among the key starters on Bloomberg’s P.P.P. Dream Team include but are not limited to Dan Doctoroff; the Mayor’s chief economic advisor and multi-hat wearer, Megan Sheekey; President of the Mayor’s Fund for eight years and a figure who to this day plays a key role at Bloomberg Associates in the Strategic Partnerships division, Dennis Walcott; Chancellor of the New York City Department of Education, Adrian Benepe; Department of Parks Commissioner, Kathryn Wilde, C.E.O. of the Partnership for New York City Office, Amanda Burden; City Planning Commissioner, Patti Harris; Deputy Mayor of New York, and Mark Page; Bloomberg’s Budget Director.

Four prescriptive, fundamental guidelines which informed all of Bloomberg’s 21 major P.P.P.s are disclosed through the Bloomberg Philanthropies website, authored by none other than the aforementioned Megan Sheekey. First, a Partnership needs to “Ensure Capacity”. Put simply, it refers to the necessity of having numbers across operations; bespoke staff have to ensure compliance and tirelessly act as the liaison between the city and its private partners. Second, “Define Opportunities”: clear goals that are comprehensible and realistic now can always be expanded upon further down the line upon the success of the P.P.P. Third, “Engage Partners”; arguably the most integral of steps: “City officials should not look to the private sector as underwriters to fill budget gaps, but as allies in building strong communities”. Sheekey, in echoing a successful Partnership Structure, maintains that it is vital to give equal footing to all entities: the more you include them, the more receptive they’ll be to seeing out the partnership successfully. “Establishing Structure” is the next step; downsizing, upscaling, expanding or minimizing the overarching initial Structure and meticulously deciding the “lifetime” of the project as discussed earlier is particularly key -- ideally, the Partnership lives on to span several generations. Finally, “Communication” is inscribed as the final step: communication between the partners, communication to the potential beneficiaries, communication between federal overlords and town locales -- countless P.P.P.s go awry by spurning the installation of a system that delivers simple updates and memos to stakeholders (Sheekey, “Building Blocks To Effective Public-Private Collaboration”).

While they largely operated behind the scenes in conjunction with their boss and various organizations, the relentless efforts of these people -- and the freedom they were given -- are to thank for some of the most successful P.P.P.s operational today. The “Collaborative City” report reveals that Bloomberg’s cabinet found themselves conjuring up Partnerships to service five pivotal sectors: “Providing Services”, “Addressing systemic issues”, “Building platforms”, “Innovating by Experimenting”, and finally “Responding with Agility”. In utilizing this framework, we can explore some of Bloomberg’s most resoundingly era-defining Partnerships, as well as ones that, for reasons pertaining to political hindrance or sheer obstinance, weren’t as successful. In tying the Partnerships to both the zeitgeist of New York at the time, and cushioning them with policies of the Mayor’s, greater truths and revelations about P.P.P.s and their interesting synthesis with societal issues emerge. A prevailing paradigm of “gaps” that needed to be closed emerged; this reappears with the same vigor that the word “bankrupt” does in articles about the city at the time. Closing the “silo gap”, “resource gap”, “flexibility gap”, and “risk gap” were of utmost priority to the administration -- they were consanguine in recognizing that these voids were implacable without the assistance of the private sector’s aid.

Yet, a question arises: can this prescriptive P.P.P. method have equal bearing on social programs as it would on mechanical construction projects? Does that “human factor” render a more perplexing success rate? In briefly touching upon a number of Bloomberg’s initiatives and examining their legacies, we can progress to answer this question. The following sector-based breakdowns focus on three key P.P.P.s that have come to define the city we know today. Certain noteworthy, landmark P.P.P.s like the execution of the Citi Bike program have consciously been omitted due to their being bereft of the status as a uniquely New York-originated initiative: bicycle rideshare programs had been omnipresent in a number of European and North American cities prior to their arrival in New York.

VIII. The Environmental Initiatives: P.P.P.s Blossom Under Bloomberg.

It is no secret that Bloomberg was an environmentalist. In curating his vision for an altruistic, greener city, his attention shifted to the topographical landscape of New York. In meeting these goals, Bloomberg immediately set one of his most trustworthy comrades, Adrian Benepe, to the task.

John Donahue, in an extensive Harvard Business School case on “Adrian Benepe’s Challenge”, outlines the prior context succinctly: “New York's public parks, brought to their magnificent peak by the legendary Parks Commissioner Robert Moses in the mid-20th-century heyday of direct government activism, were in disarray in a new era of public-sector austerity. As the City's hard-pressed government found itself short of money and manpower, the parks from the iconic Central Park to neighborhood playgrounds grew dingy and dangerous”.

Restoration efforts, sanitary measures, and general cleanliness needed to be enforced -- but with what budget? Benepe’s mission was to effectively source funds and coerce New Yorkers to “re-care”, so to speak, about the green spaces that environed them. Previous commissioners had tried to fuse the public and private in the past, though to little avail. Benepe realized two pivotal sources, both of which were abundant in New York, were key to providing some sort of remedy for the decrepit parks: volunteers and capital. Through a “Partnership for Parks” initiative that was highly publicized, “35,000 volunteer-hours” were sourced for just the clean-up of Central Park. To further decentralize this effort, mini-corporation-like organizations were erected to accommodate each green space: The Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, the Battery Conservancy, the Randall’s Island Sports Foundation, the Madison Square Conservancy, and the Riverside Park Fund were but a few of the dozens of bespoke companies set up for the sake of their eponymous parks (Donahue, p.12). These various spin-offs from otherwise generic City Parks Department was a laissez-faire gesture: let businesses, philanthropists, individuals, volunteers and organizations from that area look after the space they interact with or around daily. Benepe himself had a relentless schedule, moving from gala to charity function to office meeting, all within the course of a day. Yet, it was a success: Private partners, from bulge-bracket banks to local sports organizations, raised a total of “$50 million to improve, maintain and run programs in New York’s parks” (Donahue, p.14). Benepe leveraged the high-net worth individuals who lived within a stone’s throw of Central Park and oversaw the Central Park Conservancy morph from an “informal focal point for volunteers” to a “major civic institution” (Donahue p.12). Benepe was a board member of “53 private organizations”, all of which drastically varied in size. When he wasn’t rubbing shoulders with millionaires in the most expensive ZIP-codes, he was on the ground, providing strategic plans to his volunteers and junior staffers. His goal, beyond fundraising, was to entrench a Wall Street-like mentality, with the parks acting as major corporations. “Among the benefits the partnerships have given us, one of the biggest has been helping us think more like the private sector”. (Donahue, p.15).

While the numbers point to the programs being a concrete success, the ugly portrait of inequality also becomes more stark. By 2003, 55% of parks facilities in Manhattan had at least one private partnership group, whereas Queens and The Bronx had 26% and 29%. Manhattan parks had a much higher probability of attracting multiple partners, whereas outer-borough P.P.P.s often couldn’t manage to bring glitzy partners on board. Moreover, the graph in Fig. 8 assuredly displays that park conditions rapidly improved, though discrepancies as to how the Partnerships spread emerged. While no significant contemporary data exists to debunk this claim today, one could posit that, given inequality continues to plague Manhattan’s relationship to its four other Borough neighbors, the story is not drastically different.

Fig 8 (L) Park Condition Ratings by Park District in Bloomberg’s First Full Year, 2002. Extracted from “Parks & Partnership in NYC: Adrian Benepe’s Challenge”, John Donahue.

Fig 9: Quality Measures for New York City Parks. Extracted from “Parks & Partnership in NYC: Adrian Benepe’s Challenge”, John Donahue.

The data speaks for itself: a hearth of parks within Manhattan feature in the 93-100% acceptable range, while the majority of the parks that fall within the lower-two darker-blue registers are located in Brooklyn and Queens. That being said, the quality measure average percentile for the overall condition of parks (Fig. 9) has been on the increase, and Bloomberg & Benepe’s work in creating micro-corporations is not only resolute and successful, but a precedent that continues into this day.

Mayor De Blasio’s most recent “NYC Parks: Report on Progress 2014-2016” indicates that the decentralized-spaces approach taken by his predecessor has resulted in the most safe, clean, accessible, and “smart” series of parks in the city’s history. Linchpin directives by De Blasio include the Community Parks Initiative, extensive volunteer programs pioneered by Benepe, and digitizing parks by means of social media outreach, which is to say that each park conservancy -- another initiative of the P.P.P. -- has a visible, reachable team representing it online. De Blasio, alongside Benepe’s successor Mitchell J. Silver, inaugurated the “Anchor Parks” Project in late 2016, an effort to utilize parks as community centers in impoverished neighborhoods. This section, however, concludes that much has to be done; “data-driven strategies...we will work to acquire and develop private land” (“NYC Parks: Report on Progress 2014-2016, p.35). Still, the pioneering reorganization of parkland done through Bloomberg and Benepe’s efforts are the shoulders from which the excellent state of outdoor spaces today stand from. Highlighting inequality, rather than veiling it, should be a goal of any P.P.P.

Two key other environmental P.P.P.s include the MillionTreesNYC Program and, arguably one of the most symbolic examples of reappropriation of a disused feature, the High Line project. Both of these green-oriented P.P.P.s exemplify innovative tactics to accrue greenery within a city that is famously known as the concrete jungle.

The MillionTrees program, which sought to increase the number of city trees by 20%, was orchestrated by Benepe’s Parks & Recreation Department as well as the New York Restoration Project, a charitable organization run by Bette Midler. The “Collaborative City” report details that the Partnership Agreement balanced duties effectively: 70% of the planned trees would come from the public City government, whereas the remaining 30% would be allocated by the private sector. The introduction of smart-city mapping technology co-hosted by both sectors would map out and index the number of new trees planted. The Mayor’s own Parks-budget fund alongside an additional $25 million raised by the private sector went towards these arboreal efforts. Amy Freitag, head of the New York Restoration Project, explained part of the rationale behind the P.P.P.’s adoption. In delegating responsibility to the private sector, corridors of opportunity opened up in spaces that were not usually permissible for the City to plant on (“The Collaborative City, p.23). The effort was signalled as a unifying, pleasant, and accessible endeavor, with many volunteers dedicating their planting to a loved one or organization. In a moment of across-the-aisle goodwill, Mayor De Blasio invited Bloomberg to be present for the millionth-tree planting, completed in November 2016 at the Joyce Kilmer Park in the Bronx (“Milliontreesnyc.org”).

In 1999, Joshua David and Robert Hammond, two active community members, vehemently opposed then-Mayor Rudy Guiliani’s plan to demolish a long, winding monorail line that snaked alongside the West Side of Manhattan. While Master Builder Robert Moses, at the close of his term as City Commissioner and gentrifier extraordinaire, had mandated the mass-renovation of the West Side Highway, this overhead train line had escaped his wrath to become a rotting, weed-infused “eyesore”. Hammond and David, to obstruct any doing away of the relic, established a small committee known as the “Friends of the High Line” (“The Collaborative City, p.34).

What Hammond and David didn’t know was that Bloomberg had a vision to transform a steely, neglected monolith into a vibrant, neighborhood-defining green space. In the mid-2000s, Amanda Burden and Adrian Benepe, Commissioners of City Planning and Parks respectively, fused their knowledge to unveil a plan wherein the Friends of the High Line, in conjunction with federal approval, could bring Bloomberg’s vision to life. This was no miniscule task, however -- the serpentine rail-line, which had been primarily used to transport cargo, meat, dairy and produce (“History”, “High-Line.org), stretched from 14th street twenty blocks or so north. Bloomberg set to work by carving out the “West Chelsea Special District” rezoning order, and hosted an “Ideas'' competition, wherein 720 proposals from architects and private-consultancy firms around the world were reviewed (“History, “High- Line.org”). The funding process for such a visible, trendy project drew hundreds of banks, sponsors, family foundations, and individuals to cater to the $110 million Friends of the High Line fund. While the initial $150 million was sourced from the Mayor’s Office with additional federal support to pay to private construction contractors, this privately-sourced Friends of the High Line fee was instrumental in adorning the fauna and aesthetic of the walkway.

The first segment opened in 2009, permitting pedestrians -- be they tourists, locals, or simply commuters looking to take a detour -- to visualize the surrounding West Side in an entirely novel way. The second wave of segments opened in 2012 and 2014 respectively to an N.Y.C. public that was already in rapturous support. The MetLife Foundation, Diller-Von-Furstenberg Family Foundation, Google -- who opened an office nearby --Calvin Klein, UniQlo, Toyota, AT&T and a host of other household names committed thousands of dollars to promote volunteer programs, plant vegetation, and cover unanticipated costs that occurred during the grandiose renovation. It hired scores of workers, and the Friends of the High Line office, situated nearby in Chelsea, remains an influential force in attracting art installations, special events, and botany enthusiasts: High-Line.org cites that the structure is home to “500+ species of plants and trees”. To Bloomberg however, the greatest asset of the High-Line was its pollinating effect on its surroundings. In accordance with his penchant for rezoning, In Thomas Demonchaux’s amusingly titled New York Times piece “How Everyone Jumped Aboard a Railroad to Nowhere” from 2005, the author recounts how the initial vision for the High-Line was “quixotic at best”. Yet, through sequenced-planning, the promotion of what started out as a grassroots, quiet community support group, strategic employment, a willingness to engage the private sector, the High-Line is not solely a walkway but a cultural focal point in New York’s modern history. But what did Joshua David,the originator and co-founder of the Friends of the High Line, have to say about the rollercoaster his dream to preserve an old rail line ended up taking? “[The High Line]...is a symbol for what New York can do -- the creative and innovative power of the city....Everybody now looks to this project as a model.”

Fig B : The High Line, circa 1980-1985, Extracted from “The High Line Before the High Line”, Buildllc.com.

Fig B2: The High Line Computer Visualization, 2019. Extracted from “The Ultimate Guide To The High Line”, Jenna Scherer.

IX. Social, “Human Factor” P.P.P.s Provide Mixed Outcomes

The reception and legacy concerning Bloomberg’s socially oriented P.P.P.s was a little more heterogeneous. While the jubilant “Collaborative City” report has a celebratory tone -- and rightfully so -- it is worth mentioning that P.P.P.s are not the be all-end all remedy to the issues plaguing society. Bloomberg’s social impact P.P.P.s were transformative, innovative, and above all, managed to narrow down issues that are otherwise implacably generic and therefore menacingly invisible at times. His administration should be applauded for having the audacity to tackle said dilemmas with approaches that broke away from the mundane.

One particular example of this is the utilization of Social Impact Bonds at Rikers Island prison. The controversial facility is a metonym for misdemeanor, crime and punishment within New York, though from Guiliani’s reign onward it became increasingly associated with flaws in the justice system. Bloomberg and co. honed in on the facility with one statistic in mind: “nearly half of all adolescents in city jails wind up back in the system within a year of release” (“The Collaborative City, p.61). This phenomenon, known as recidivism, wherein freed-inmates relapse into crime, had become a pervasive issue within several N.Y.C. communities. To tackle such a multi-layered problem, Bloomberg’s administration announced the “ABLE” program with accompanying social-impact bonds.

The partner in question was no small fish: it was none other than the preeminent titan of New York’s banking world, Goldman Sachs. The ABLE program was the first of its kind in the entire country -- social impact bonds had no precedent whatsoever, especially not in a country that has the highest population of incarcerated individuals. For G.S., the program struck a heartfelt tone from a public relations standpoint: The world’s most renowned bank, delivering $9.6 million for a project concerning recidivism, in partnership with the public sector. The economic motivation of the program beyond offering counseling, group therapy and classes for inmates aged 16-21 to steer them away from recidivistic behavior was a premium one: “If the recidivism rate dropped by 20%, New York City would save as much as $20 million in incarceration costs after repaying the loan [to us]” (“First U.S. Social Impact Bond Financed by Goldman Sachs”). In principle, the notion of infusing a public quagmire with intense private capital seems like a brilliant remedy.

However, the effects were difficult to measure. Certain critics blasphemed the program as being tone deaf, citing that social impact bonds were the new “silver bullet” to protect city governments from being scapegoated for not spending enough on criminal justice reform (“NonProfit Quarterly”). The Vera Institute of Justice, tasked with monitoring the program independently, concluded that the program failed and that recidivism rates did not alter for the better. According to Donald Cohen and Jennifer Zelnick of Nonprofit Quarterly, social-impact funds are fundamentally configured in a way that does not set them up for long-term success, and “divert investments that could be used in other ways”, such as bread-and-butter philanthropy. However, some positives were extracted: Justin Milner et. al. at Urban Wire found that the same Vera report indicated many youths registered “programmatic milestones found in prior studies to be associated with positive outcomes”. They conclude by mentioning that this attempt was better than the alternative, and that critics of the program should expect mixed results within such a complex and “disruptive” environment.

The Rikers Island Social Impact Bond program was the centerpiece of many other reforms within a larger P.P.P. agenda of Bloomberg’s known as the Young Men’s Initiative (YMI). To this day, this could be qualified as one of the most difficult P.P.P.s to evaluate, primarily because it deals with the “human factor” that is so elusive to quantify. In what could be considered a remedial and apologetic measure in the wake of controversial “stop-and-frisk” policies, a Bloomberg speech in August 2011 announced the commencement of a set of programs to “tackle persistent problems facing young Black and Latin males''. The program would be funded through a hybrid of capital from the Mayor’s Office, the Open Society Foundation, with further micro-partnerships with over 150 local community organizations and businesses (p.39, “The Collaborative City”). Programs under the Y.M.I. included the CUNY Fatherhood Academy; which enables young fathers earn requisite education and job skills, NYC Cure Violence; which provides specialized courses in conflict management and reconciliatory exercises, and the Young Adult Internship Program; which fast-tracks summer placements to young, unemployed men of color. The Mayor would receive an airtight monthly report detailing progress so as to act on any program that seems ineffective and futile.

Two significant problems plagued the YMI P.P.P. Firstly, enthusiasm and enrollment in the program started to drop. Sally Goldenberg of Politico found that while the YMI managed to bolster 771 men to graduation and concrete employment, it still fell short of it’s 1,281-man goal. The disappointing figures concerning job training enrollment, training-completion, and job placement in the next two years fell successively (“Bloomberg’s anti poverty initiative shows mixed results”, Politico). The second and most significant problem lingering within the innate cause of the YMI is that critics essentially perceived it to be a Catch 22: Guiliani and Bloomberg’s bellicose police force was arresting scores of Black and Latin descent males on the grounds of stop-and-frisk -- a program which only formally ended in 2013 upon being rendered unconstitutional, as mentioned earlier. According to some, The YMI and Rikers Island Social Impact Bonds were efforts warranted by systemic, sordid practices that the Mayor and his Police Commissioner were presiding over and causing. Granted, dozens of criminals -- especially those who end up with sentences that have them transported to Rikers Island -- were indeed guilty of crimes committed, and major offences (See Figure 7) did decrease. Yet Bloomberg did not curry favor with left-leaning democrats and criminal justice reform-aficionados, whom cite a New York Civil Liberties Union dataset in Fig 11 as justification to be outraged:

Fig 11: Number of Reported Stops by Year, 2002-2019 & Annual NYPD Report Breakdown.

The issue of crime for any Mayor in any city is a polymorphous, multi-layered challenge, and for a city the size and scale of that of New York, Bloomberg certainly had good intentions in responding to the deeds of stop-and-frisk with widely-encompassing community programs. Additionally, it merits mentioning that the decrease in stop-and-frisk stops exhibited from 2011 henceforth could also be a function of the simple deterioration in crime, as crime rates and major offences touched upon in Fig. 7 did indeed diminish. The legacy of the YMI is mixed, although major critical successes of it are still in practice under the De Blasio administration. With thanks to the sacrifices and public relations nightmares Bloomberg had to endure, De Blasio has had the relatively calmer task of surgically removing the most functional aspects of the YMI and incorporating them into his own repertoire. One fantastic repercussion of the YMI is its sibling. The Young Women’s Initiative, launched by City Council speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito in October 2015, aims to apply the best social formulae identified in Bloomberg’s YMI to the plight of girls and women aged 12-24, with “a spotlight on structural inequality, health, education, mobility, and criminal justice” (Burger, “Council to Examine Young Men’s Initiative). To declare that Bloomberg’s socially targeted P.P.P.s were a holistic failure would certainly be refuted by one of his proudest, yet not as discussed, accomplishments.

In establishing the Center for Economic Opportunity (C.E.O.) in 2006, the Mayor managed to designate an unprecedented executive-level office that was solely dedicated to the welfare of impoverished, unemployed, and seemingly unemployable individuals. This particular initiative is riddled with novel and experimental approaches that break with tradition. Components include Jobs-Plus; which provides government-housed people with streamlined, expert-level training and access to job fairs, SaveUSA; which offers cutting-edge financial assistance to low-to-moderate income families to develop budgeting patterns and intertwine savings accounts with people who would otherwise live paycheck-to-paycheck, and Project Rise; which connects young adults to corporate experiences and matches them with employment commensurate with their GED or lack thereof. Veronica White, the Center’s Executive Director and Founder, is vocal in her gratitude towards the private sector. Initial projects taken on, she says, were “very controversial”, though the “totally private dollars” ‘mollified” some of the internal City Hall opposition (p.58, “The Collaborative City”).

As with the green-space set of P.P.P.s, realms that were normally hindered by the constraints of private property suddenly opened up to City-access. Furthermore, the notion of a “positively spirited” initiative has time and time again proven a boon to entice various private family offices and philanthropic organizations to get involved. Funds to fuel the C.E.O. were sourced from a private consortium made up of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Rockefeller Foundation, the New York Community Trust, and many more. Recognition for the pioneering program was abundant and highly publicized, with the Obama administration awarding Bloomberg a Federal Social Innovation Fund, a type of bestowed-grant that exemplifies how the upper registers of government can play an active role in emboldening city-specific initiatives. “The Collaborative City” hails the C.E.O. 's venture as a bewildering success, with 450,000 individuals served, 30,000 job placements, 10,000 paid internships, with over $100 million in New York citizen tax dollars directly being accounted for. The calendar year 2012 -- Bloomberg’s ten year anniversary as the city’s manager -- brought about near-record low unemployment rates (De Avila, “New York Jobs Report ‘Exceeded All Expectations’”), and the C.E.O.’s operationality can’t be overlooked as a major contributor to this statistic. If imitation is the best form of flattery, then the C.E.O. has received a flurry of complimentary gestures, as Memphis, San Antonio, Kansas City, Newark, Tulsa, Newark and more have adopted stimulus programs that emulate the P.P.P. structure and cause of the C.E.O. To date, the C.E.O. remains an integral megaphone through which city-wide policies are clearly communicated. The NYCOpportunity website, the web-based home of the program, is an agglomeration of social networking, news, and opportunity -- three fundamental pillars of familiarity in today’s aeon of transparency. Courtney Hawkins, the SVP of a non-profit that worked closely with the C.E.O. elucidates the scalability of Bloomberg’s most refined social P.P.P. in saying that “A lot is said about using evidence-based practice...but some of what has to be done is build evidence around practice...and sometimes you’ll be successful and need to replicate” (p.60, “The Collaborative City”).

While Mayor De Blasio may tout his social measures as being successes, his Office has benefited from the experimentation, sacrifice, compromise, and brilliance of the Bloomberg administration applying positively-disruptive solutions to immiscible problems that no clear cure exists for. While the Young Men’s Initiative and Rikers Island Social Impact Bonds were met with mixed reception and success rates, Bloomberg struck a chord that few other Mayors were able to, as Hawkins suggests, in building evidence around practice as opposed to the other way around. The Center for Economic Opportunity, however, can objectively and numerically be hailed as a major triumph in reanimating the outlook of employment opportunities in an equitable manner.

X. The Utilization of P.P.P.s On The Largest Scale Possible

Image: https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2019/02/hudson-yard-billionaires-fantasy-city.html

The final section concerning Bloomberg;s P.P.P.s concerns large-scale, revolutionary projects that changed the ribosomal structure of New York forever. The Hudson Yards development replete with its 7-Train extension, the Hurricane Sandy Relief effort, and the NYCBigApps competitions have all transformed the city, either saliently or subliminally. The most visible of these P.P.P.s is unequivocally the addition of a new neighborhood to Manhattan: the gargantuan urban sprawl that is arguably the most enduring, symbolic and grandiose piece of Bloomberg’s legacy in the city.